In What is Harmony (Pt. 1), we explored the fundamental concept of chords and scales. As you tune your ears to these distinct harmonies, it’s apparent how they can structurally make or break a song. Understanding their interplay is akin to understanding the language of music itself. In part 2, we establish a relationship between the two and explore further concepts surrounding scale degrees and chord progressions while analyzing them through some of your favorite songs!

Scale Degree

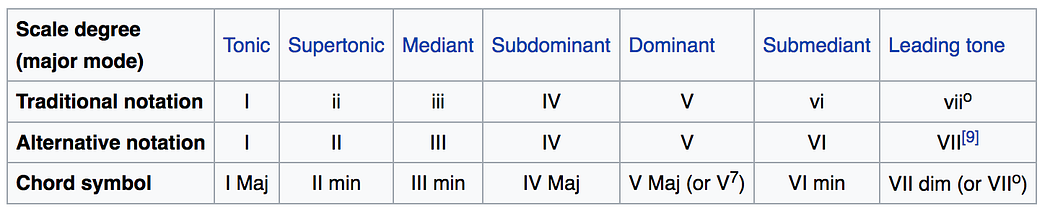

The numbering used for each note in the scale is called the ‘scale degree.’ For instance, in the C major scale, scale degree 1 is the C note, the D note is 2, and so on. There are several ways to refer to scale degrees. A very common way for chords (as scale degrees) to be labeled in a scale is through Roman numerals or specific terms assigned to each degree. In music theory, the names and numerals used for scale degrees are as follows:

Major chords are represented by capital Roman numerals, minor by non-capital, diminished by non-capital followed by a small circle, and augmented by capital and a plus (+) sign.

With each scale degree, you can build a diatonic chord and determine its quality (major/minor/diminished/augmented) using the intervallic patterns discussed in pt. 1.

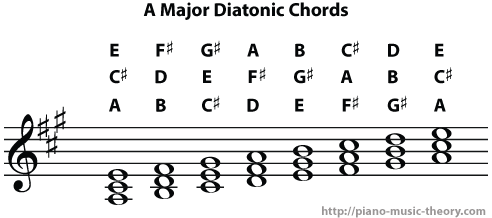

Here’s a visual example of how triads on an A major scale are represented:

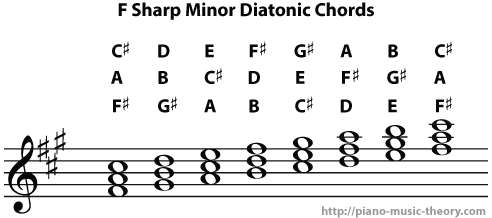

Here’s an example of triads formed with a F# minor scale:

As you can see, both A major and F# minor use the same notes because every major scale has a relative minor with the same notes and chords but use different starting points. Here’s a video to help you understand this further:

Now that you are aware of what makes a scale, and how they relate to chords and scale degrees, you can apply this knowledge to blend exciting elements and create beautiful harmonies within the context of music. But how exactly do you craft a piece of music? Where do you begin? This is where progressions come in — the same way we phrase anything melodically, instruments rely on progressions to create a fuller and dynamic musical experience.

Chord Progressions

Chord progressions refer to a series of chords played around a key. For many composers and songwriters, crafting a song often begins with chord progressions, making it crucial to become familiar with them. To deepen this understanding, it’s essential to grasp the concept of resolving through a cadence.

Cadence

A cadence is the ending of a musical phrase. Reaching the tonic (scale degree 1) from a chord or note imparts a sense of conclusion to that phrase. This musical phenomenon is termed ‘resolution’ or ‘resolving.’ A ‘perfect cadence’ occurs when chords transition from scale degree 5 to 1, or dominant to tonic, earning its name from its conclusive feel. Another frequently used cadence involves moving from scale degree 4 to 1, or subdominant to the tonic, known as a ‘plagal cadence.’ This type of chord resolution imparts a smoother and more tranquil feel.

Take a look at this example:

Perfect cadence: G major to C major (V-I in the key of C major)

Plagal cadence: Bb minor to F minor (IV-I in the key of F minor)

Cadences provide various methods for constructing chord progressions that offer a satisfying sense of resolution. Take a look at this video to observe the different cadences that can be applied within a song/piece:

While cadences create the necessary stopping points, a progression is where a musician can really take control of the structure, form, and feel of the song. It works around using different scale degrees and creating harmonies that could lead to distinct resolutions.

Let’s take a look at some of the most prominent progressions in songs and other progressions used widely throughout the evolution of music:

The Pop Standard (major scale)

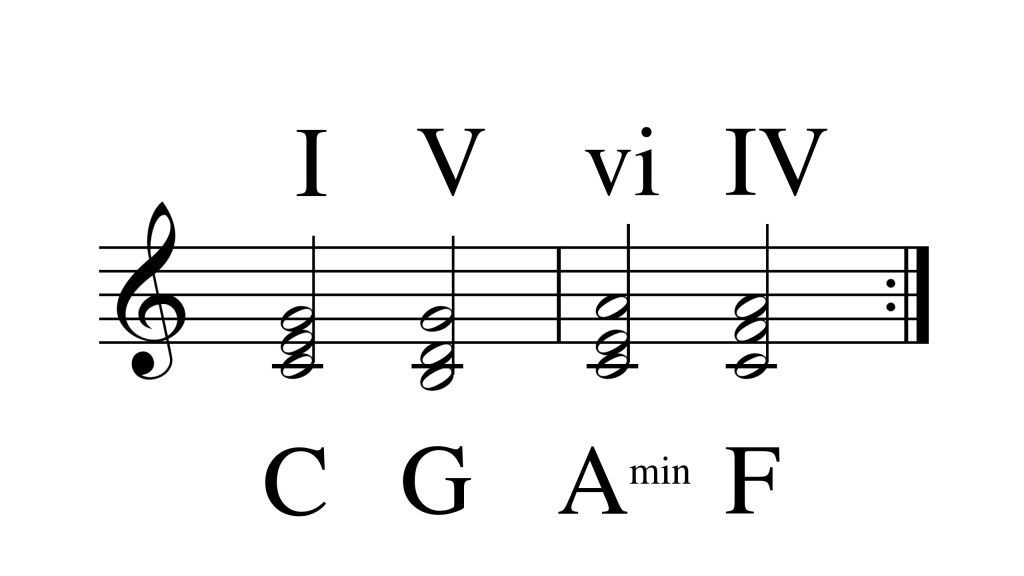

I — V — vi — IV

This chord progression is the most commonly used one in pop music. For instance, in the key of C major, this progression unfolds as C major — G major — A minor — F major. The shift from C major to G major introduces harmonic tension, as it moves away from the stable tonic. It eventually arrives at F major and loops back to C major. This movement creates a plagal cadence (IV — I), and resolves back to the pleasant sound of I.. This recurring interplay of tension and release contributes to the widespread use of this chord progression.

Here are some examples of songs that feature it:

‘Don’t Stop Believing’ by Journey ‘Someone Like You’ by Adele

‘Demons’ by Imagine Dragons ‘All too well’ by Taylor Swift

‘Let It Be’ by the Beatles ‘Wrecking Ball’ by Miley Cyrus

The list doesn’t end here; to familiarize yourself with this progression, here are 103 songs (!) that use the progression 1–5–6–4 in different orders:

The ‘Redbone’ chord progression (minor scale)

i — VI — VII — i

‘Redbone’ is an RnB/soul track by Childish Gambino, produced by Ludwig Göransson. In the key of D minor (i) — during each occurrence of the main riff, the chords follow the sequence Bb major (VI) — C major (VII) — D minor (i). This smooth upward movement of chords, progressing note by note, leads to resolution. The consecutive use of major chords, along with the resolution, imparts a tone that is somewhat not melancholic, proving how dynamic minor keys are.

Take a look at few other minor chord progressions you should know: